Module 2: Feedback Loops and Causality – Lesson 2

This lesson is just one part in our series on Systems Thinking. Each lesson reads on its own, but builds on earlier lessons. An index of all previous lessons can be found at the bottom of this page.

Why Systems Surprise Us

One of the defining traits of complex systems is that they rarely behave on our schedule or in neat proportion to our efforts. We push and pull, expecting immediate and equal reaction, only to find the system sluggish in one moment and explosive in the next. These surprises are not accidents—they arise from two core dynamics that underlie much of system behavior: delays and non-linearity. Delays stretch the gap between cause and effect, creating instability and misjudgment. Non-linearity bends the relationship between input and output, making “more” sometimes mean less, nothing, or far too much. To see these dynamics clearly is to avoid the traps that catch even seasoned decision-makers.

Delays: The Time Gap That Distorts

A delay is the lag between action and visible outcome. Some delays are material: crops take months to grow, shipments take weeks to arrive, muscles take years to build. Others are informational: a market trend isn’t noticed until quarterly reports come in, or a community doesn’t recognize cultural change until it has already happened.

The challenge with delays is that they distort how we perceive feedback. If you act as though effects are instantaneous, you risk overshooting. Consider adjusting the thermostat on a slow-to-heat system: turn it up too quickly and you’ll find yourself sweltering when the room finally catches up. Similar overshoot-and-collapse patterns appear in housing markets, hiring cycles, even personal habits like dieting. Delays make systems feel unresponsive at first, then suddenly overwhelming, leading to oscillations that frustrate our sense of control.

Non-linearity: When More Doesn’t Mean More

Non-linearity describes relationships where input and output are not proportional. We often imagine systems as straight lines: double the effort, double the result. Reality is more curved. In some cases, nothing seems to happen until a threshold is crossed—think of ice melting, or a social movement suddenly achieving critical mass. In others, the opposite occurs: early gains come easily, but each additional push yields less, as in diminishing returns from fertilizer on crops or ad spend on consumer awareness.

Non-linear patterns also produce runaway dynamics: the compounding of interest, the viral spread of ideas, or the cascade of a financial panic. Many systems trace S-curves, where growth accelerates sharply after a tipping point and then flattens as limits appear. These curves confound our straight-line instincts and demand that we look for turning points, thresholds, and ceilings rather than assuming the future will simply extend the past.

Strategies for Seeing the Hidden Structure

The first step in working with delays and non-linearity is learning to recognize them. This requires a shift in questioning:

- Ask about timing. When does the effect of this action actually arrive? If it’s not immediate, a delay is present.

- Test proportionality. Does twice the input yield twice the output, or does the curve bend?

- Look for limits. What natural ceiling or floor might constrain growth or collapse?

- Watch for oscillations. Regular swings in performance or conditions are often the signature of a lagged response.

These questions act like lenses, bringing hidden structure into focus. Even without numbers, you can sketch whether a system is prone to overshoot, plateau, or rapid shifts. Systems thinking does not require perfect prediction—it requires better anticipation.

Leveraging Insights from Delays and Non-linearity

Recognizing these dynamics is only half the task; the real value comes in how we respond.

- Delays teach us to act with patience and foresight. Once we see the lag, we can design interventions that anticipate future outcomes rather than chasing present symptoms. This helps us avoid overcorrection, sustain strategies long enough to pay off, and time our actions so they stabilize rather than destabilize.

- Non-linearities teach us to look for leverage. By mapping where thresholds, tipping points, and limits lie, we can place small actions where they have outsized impact, withdraw effort where returns diminish, and prepare buffers against sudden runaway dynamics.

The payoff is not clairvoyance but foresight. A systems thinker who recognizes delays and non-linearity can anticipate oscillations before they emerge, redirect resources before waste sets in, and prepare for tipping points before they surprise others. In practice, this often means the difference between firefighting after the fact and shaping outcomes in advance.

Real-world Examples

Climate Change

Carbon dioxide released today will continue warming the atmosphere decades from now, a material delay built into the physics of the Earth’s systems. Meanwhile, non-linear tipping points—such as the collapse of polar ice sheets—threaten to accelerate change far beyond our incremental expectations. The lesson: waiting for visible effects before acting ensures we arrive too late.

Supply Chains

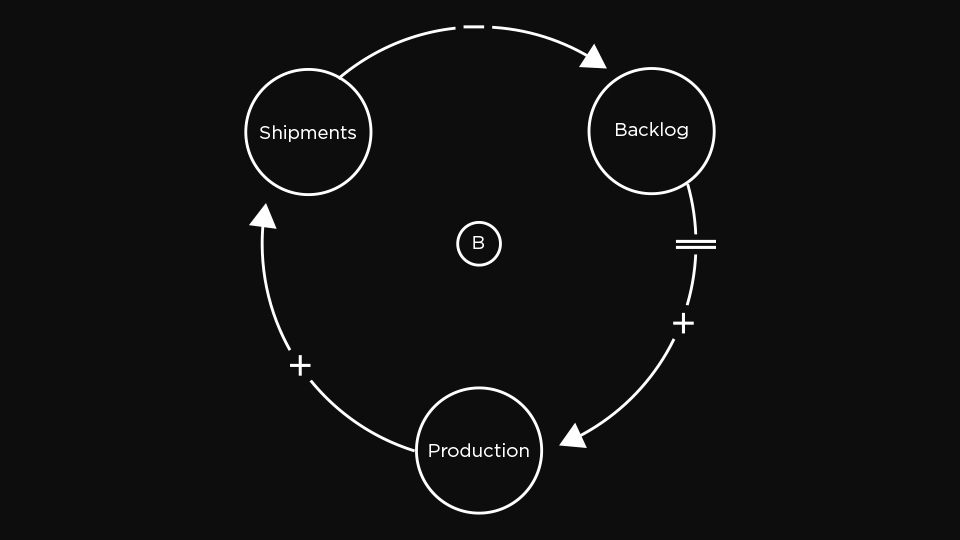

Manufacturers facing increased demand often over-order, only to be left with excess stock when the delayed shipments arrive. The relationship between supply and demand isn’t linear; costs spike when warehouses overflow, amplifying the problem. Here, both delay and non-linearity conspire to produce the notorious “bullwhip effect.”

Branding and Marketing: Advertising Spend

A new brand invests heavily in advertising, expecting immediate sales. When results lag, managers either panic and cut budgets or recklessly double down. What they miss is the delay: awareness and trust take time to build before they convert into purchases. They also miss the curve: initial gains from ad spend are dramatic, but returns diminish as audiences saturate. Brands that understand these dynamics avoid knee-jerk reactions and instead plan for the long arc—sustaining effort until the system catches up, and shifting resources when diminishing returns appear.

Notation: Marking Time and Curves

In causal loop diagrams (CLDs), delays are marked with a double slash // on the arrow connecting cause to effect. This simple symbol reminds us not to treat the link as instantaneous. Non-linear relationships are harder to capture with a single symbol; we often annotate the arrow with a note like (diminishing returns) or describe the shape in words. The goal here is not precise mathematics but disciplined attention: naming delays and curves keeps them from slipping out of view.

Thinking in Time and Curves

Delays and non-linearities explain why systems so often defy intuition. They ask us to think in rhythms rather than snapshots, and in curves rather than straight lines. When you recognize them, you stop expecting instant payoff, you avoid the trap of linear projection, and you begin to anticipate the arcs of change more accurately. In short: delays train us to respect timing, and non-linearity trains us to respect proportion. Together, they give us a more honest map of how systems move through time—and how we might act within them wisely.

Course Index

- Module 0: Introduction to Systems Thinking

- Module 1: Components of Systems

- Module 2: Feedback Loops and Causality

- Lesson 2.1 — Reinforcing and balancing loops

- Lesson 2.2 — Delays and non-linearity